Since 2019, more than 8,500 migrants have reached the coast of the archipelago on patera boats. Most of them are of Algerian origin and, increasingly, sub-Saharan Africans. They are people in transit to Europe who dare to take the second

deadliest route in Spain and put the Balearic reception system to the test

Antonia Gil and Virginia Servera| Palma

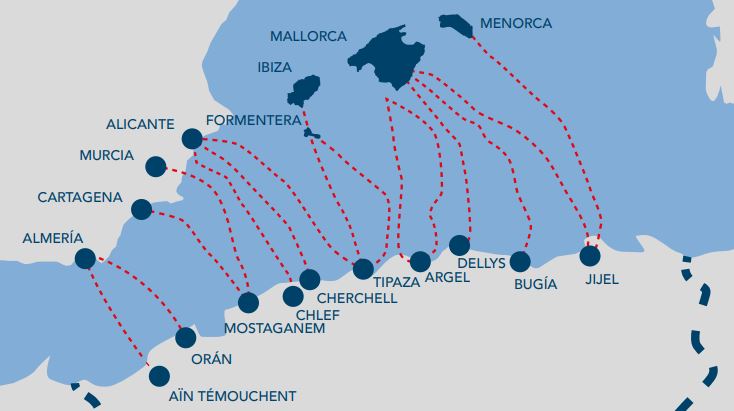

They are usually located by Maritime Rescue or the Civil Guard, generally in good health, when they reach Balearic territory; most often they are spotted in the waters of Cabrera or Colònia de Sant Jordi. About a day has passed since they left Dellys (Algeria) on board a patera -small boat- and they feel the satisfaction of having overcome the 300 km that separate them from the prosperous Europe they have in mind.

The Algeria-Balearic Islands maritime route has become more established in recent years. In 2019, 507 irregular migrants disembarked in the archipelago from the North African country, and in 2022, 2,637 disembarked in the archipelago. While some voices point out that behind this increase could be, among other factors, the diplomatic crisis unleashed by the Spanish government with Algeria when it recognised Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara in March 2022 – a hypothesis that the Interior ruled out at the time – other experts do not believe that it has had an impact on the increase in migratory flows: “Algeria has not played with migration in the same way as Morocco, which needs funds, has the whole Sahara issue and has traditionally played with opening and closing the border for 30 years”, says Helena Maleno, human rights defender, doctor honoris causa from the University of the Balearic Islands and founder of the group Caminando Fronteras (Walking Borders).

The Guardia Civil watches over the disembarkation of a group of Algerian migrants on their arrival in Mallorca. Photo: Teresa Ayuga.

Pending the definitive data, in 2023 there was a slight decrease in arrivals compared to the last two years, a fact that the secretary of the Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Rights and Freedoms of the Balearic Islands

(LIDIB) and co-author of the report ‘The reception of irregular migrants in the

Balearic Islands’, Valentina Milano, attributes to the fact that “the trafficking mafias are using the Algerian routes to

Alicante and Murcia more this year”.

From there, according to an investigation reported by El Periódico, they have the option of getting into a car to reach the Catalan border with France, where they take routes on foot to reach the neighbouring country.

Although the route to the Balearic Islands is the longest and most dangerous of the western Mediterranean route, as the organisation Caminando Fronteras warns, this does not prevent hundreds of people from setting out to sea in search of new opportunities. Most of them are young men (96 %) of North African nationality (84 %), mainly Algerians, although there are also arrivals of people of sub-Saharan origin (13 %), especially from Guinea Conakry, according to the latest report by the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid.

“There are clandestine Algerian organisations involved in embarkations to the islands. These entities have a pact with the Algerian government to let only Algerian nationals pass through”, reports LIDIB. Maleno points out that recently “the route is being used a lot by people of nationalities other than Algerian. Especially sub-Saharan people in transit” and stresses that migrants of a nationality other than Algerian travel by more dangerous methods and, as a result, there are usually more deaths among them.

More and more people would like to stay here, say the LIDIB.

Undocumented migrants in transit

They are known as ‘harragas’ in Algeria. They are “those who travel without documentation, those who ‘burn’ borders”, as described by Caminando Fronteras. Among the reasons for doing so are the precarious economic and employment situation, the lack of rights and repression by the security forces, as well as the lack of expectations of a future, according to LIDIB. “Many people leave Algeria because they have suffered strong repression with the Hirak,” adds Maleno, referring to the movement that originated in February 2019 and demanded the resignation of former president Bouteflika.

“Algeria is a country very rich in gas resources with a regime disguised as a democracy. It is a country governed by a gerontocracy, a very old political class, where the army has a very important role and a lot of interests in the gas sector. Young people flee because they see that they cannot prosper in the midst of archaic social structures,” explains Joan David Janer, professor of International Public Law and International Relations at the UIB.

The Algerian route in the western Mediterranean. Source: Ca-minando Fronteras.

The ultimate goal of those who arrive in the Balearics in these circumstances is to reach France or Belgium, “a trend that is changing; there are more and more people who would like to stay here”, according to LIDIB. “Some people have told us that they would have considered staying if it had been proposed to them because Spain is also an interesting alternative for them”, says Milano, who also holds a PhD in Law from the UIB.

Unlike the sub-Saharan profiles, “there are very few asylum seekers among Algerians”, says Luis Ciges, a lawyer specialising in migration and international protection, who puts the number of Algerian migrants who decide to settle on the island at 5-10%. For her part, Valentina Milano regrets that the resources and time are not devoted to “detecting needs for international protection (asylum) and possible situations of trafficking or exploitation at the interview stage. For women and girls, for example, physical or sexual violence within and outside the family and the risk of forced marriages, female genital mutilation, trafficking or honour crimes, among others, are grounds for persecution that entitle them to asylum,” she adds.

For women and girls, for example, physical or sexual violence within and outside the family and the risk of forced marriages, female genital mutilation, trafficking or honour crimes, among others, are grounds for persecution that entitle them to asylum

Self-organisation prevails

The mafia structures that operate in Libya, Morocco or Tunisia are not present in Algeria, where there is self-organisation among those who wish to migrate to Europe, according to Caminando Fronteras. “It happens like in Senegal, there are many people who join together, who are from the neighbourhood, fishermen who use the boats they have there”, Maleno continues.

“‘Taxi-patera’ is not the main instrument”, according to the report El muro de la indiferencia (The wall of indifference), which does reflect an increase in local groups of smugglers in recent years who offer better boats and engines with greater capacity. “There are class 1, 2, 3 (so to speak)… The more money you pay, the faster the boat, the more water and food you get… The less you pay, the longer it takes and the more dangerous the boats are. Some people have told me that they have paid as much as 5,000 euros”, says Luis Ciges.

All the people who arrive on our coasts in an irregular manner have a return file that cannot be carried out at the moment; they cannot be returned to Algeria because it does not allow them to return

An express reception

Upon arrival on the coast, and after an initial health assessment and identification of vulnerable people by the Red Cross, the migrants are handed over to the National Police for filiation. At times of maximum influx, spaces have had to be set up such as terminal number 6 of the port of Palma or the former Son Tous barracks (currently in use), recalls the LIDIB.

After police custody, which lasts a maximum of 72 hours – now only 4-5 hours, Ciges points out – the return process begins. “All the people who arrive on our coasts in an irregular manner have a return file that cannot be carried out at the moment; they cannot be returned to Algeria because it does not allow them to return, but they do leave Son Tous because they have committed an administrative irregularity (they have not arrived where they should have arrived) but they have not committed a crime,” declares Aina Calvo, the government delegate in the Balearic Islands.

“They go free. Most of them come with money in their pockets to pay for a boat ticket to the peninsula and, from there, to France”, adds the lawyer consulted, who insists that “although Spain has a return agreement with Algeria, no country accepts returns without a passport”. Apparently, it is common practice for migrants to take away their identity documents, and “this leaves Spain with no evidence for the country that has committed to readmitting irregular migrants to do so”, Janer adds.

Migrants arriving by patera boat in the Balearic Islands. Data updated to 21 November 2023. Photo: Teresa Ayuga.

The Balearic Islands’ response, under scrutiny

“At the moment in the Balearics we are fortunate to have good institutional coordination; the Civil Guard and Maritime Rescue are saving lives at sea. We have coverage for the protection of children and adolescents, including accompanied minors (MENAS), and we are trying to ensure that the management of this phenomenon is as effective as possible. This is currently the case”, says the government delegate in the Balearic Islands. Helena Maleno does not share the same opinion, saying that “the Balearic Islands do not carry out active searches as they should”. The journalist and writer also argues that it is a route that the institutions have not wanted to recognise: “Politically, making a route invisible means that you do not have an adequate reception system to respond to the people who come. The reality is that there are many dead and missing people on this route, that there are corpses of unidentified people in the morgues and in the town halls of the Balearic Islands”, she denounces.

For Valentina Milano, “reception capacities must be strengthened, both logistically and in terms of the personnel involved in the reception procedure. Only after an individualised examination can it be decided who can be returned (and therefore would have to go to a CIE) and who cannot. Now the decision is taken in an almost automated and therefore arbitrary way, excluding from being returned only women and minors in practically all cases”

A group of migrants are welcomed by a Red Cross team. Photo: M.G

The Algerian route in the western Mediterranean is the second deadliest in Spain, only behind the Canary Islands. Specifically, the Balearic part is the most dangerous area

Mare Nostrum Mare Mortum

The Algerian route in the western Mediterranean is the second deadliest in

Spain, only behind the Canary Islands. Specifically, “the Balearic part is the most dangerous area”, Maleno specifies. In the first half of 2023, 8 tragedies with 102 victims were recorded along the route as a whole, according to the Monitoring of the Right to Life on the Western Euro-African Border published by Caminando Fronteras, which counts 951 victims on the access routes to Spain during this period.

“The greatest defencelessness occurs on the route to the Balearic Islands, where we have detected that the necessary resources, including aerial means, are rarely activated to address alerts in the area. In a comparison between the route to the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, it should be noted that in the Atlantic there are more active search protocols, resulting in discrimination at the regional level in Spain”, examines the report The wall of indifference.

In a comparison between the route to the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, it should be noted that in the Atlantic there are more active search protocols

Japhet Bruchel: survival instinct

“I can still hear the shots in my head of the machine guns on the wall, since then I cannot sleep”

The journey from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe

Japhet Bruchel arrived in Mallorca in July 2018. Two and a half years passed since he left his home in Cameroon until he set foot on the island, a real “hell” that he recounts with misty eyes. “I have not been able to empty myself and say goodbye to all this, the desert, the sea, the kidnappings, since then I can’t sleep. Tatatatatatá!’ I can still hear the shots of the machine guns on the wall in my head. It’s a trauma”.

Japhet is 31 years old and has lived in Mallorca since 2018. Photos: Pep Caparrós.

Japhet is one of the 630 migrants who were rescued by the Aquarius and who arrived in Valencia in June 2018, after Italy refused them entry. “I had not decided to come to Spain, I left my country because I feared for my life. I Migrants no longer receive aid Without papers (NIE), migrants residing in the Balearic Islands cannot access practically any aid. If they go to social services, the most they will be provided with is food, according to social work professionals working with migrants. The only aid they can apply for is the Guaranteed Social Income, which is around €470. But for this, it is necessary to prove 12 months of residence in the Balearic

Islands by means of a census registration that is very difficult to obtain (it requires a housing contract, which they rarely have, since for this it is necessary to present a work contract, which they also do not have), and to demonstrate that they are economically vulnerable. “The criterion is not being a migrant, the criterion is being very poor”, argue the social workers consulted. suffered discrimination and persecution because of my LGTBI status”. His family, of Christian origin, also turned their backs on him: “They told me that I was not normal, that I needed medication, they called me a demon”.

Encouraged by a group of friends, he set off for Algeria, 2,550 km away. He never imagined what the journey, for which he paid around 3,000 euros to Europe, would bring: “We crossed Nigeria to get to Niger, by bus, motorbike, car, on foot. There, a group of armed traffickers kidnapped us”. And from Niger they were taken to Libya.

Under the yoke of the mafias

“In Libya they sold us for 1,000 euros and the women for 10,000 euros; they are worth more than men because they

will produce infinite money through prostitution. It’s unbelievable that this is happening here and they turn a blind eye,” he laments. I had no one who could pay for me,” he continues, “so I was kidnapped. To make me pay, they electrocuted me, hung me upside down, beat me every day for three months without seeing the sunlight. While they were torturing us, they called our families”. Despite this, Japhet managed to survive: “I learned some Arabic and I asked a guard for my mobile phone to take a photo and that photo saved my life. I sent it to my sister and she gradually got the money.

The price of freedom

Then he was freed in Libya: “There I met someone who was trafficking in boats and he asked me for 1,500-1,700 euros to leave”, he says. And then it was time to leave: a 7-metre inflatable boat with a 70-horsepower engine for 129 people. “These people are sending us to die,” I thought, “It was 11pm when we set sail. The captain didn’t know where he was going. We ran out of petrol. Water started coming in. People were vomiting after two days, everyone was trying to survive, each one on top of the others, looking for the best place to hang on so as not to fall into the water. At night the Aquarius arrived: “People went forward and we capsized, most of them couldn’t swim. You could hear shouts: -Save me, please! I still can’t sleep to this day. Eight people died at the time of the rescue,” he says.

When they arrived in Valencia, they were given a special residence permit and he decided to go to Mallorca. Later, he was granted asylum: “I felt free”. He currently works as a waiter in a four-star hotel and volunteers with the Red Cross as a translator to welcome irregular migrants who arrive on patera boats, to whom he recommends training: “Here, if you don’t learn the language and integrate, it’s complicated. I would like to continue studying to have my own business as an electrician”.

Japhet, photographed in s’Escorxador, Palma. Photo: Pep Caparrós.

| Migrants no longer receive aid

Without papers (NIE), migrants residing in the Balearic Islands cannot access practically any aid. If they go to social services, the most they will be provided with is food, according to social work professionals working with migrants. The |

💡 The complete report can be read in the autumn-winter edition of the Mallorca Global Magazine on your newsstands now.

Leave A Comment