Online scams are soaring in the islands: from banking fraud and fake investments to attacks on tourism SMEs. A growing phenomenon where social engineering and rapid reaction are key

His name is Alex, or at least that’s how he introduces himself. He claims to work at the bank where his victim, Daniela, is a client. He has managed to infiltrate the same thread of official messages from the bank and send an SMS warning of alleged unauthorised charges. The link appears legitimate; the tone, in a phone call, as well. The goal is simple: to obtain the login credentials to her online banking. The result is immediate: one thousand euros in *bizums* withdrawn from her account before she can stop it.

Cases like Daniela’s are increasingly common. Messages that raise suspicion, charges that don’t add up or calls that appear legitimate are now part of daily digital life. David, a young Mallorcan, discovered it after seeing several payments on his card under the concept “Apple Music”, a service he has never used. In both cases, the starting point is identical: a criminal managed to obtain part of their information or knew how to manipulate them into providing it.

To understand how these networks operate in the Balearic Islands, Mallorca Global Mag spoke with the National Police officers specialised in investigating this type of crime: the Economic Crime and Technological Offences Group, part of the Provincial Judicial Police Brigade. From Palma they work in coordination with the National Cybercrime Unit, with other police headquarters in the country and with international organisations such as Europol and Interpol.

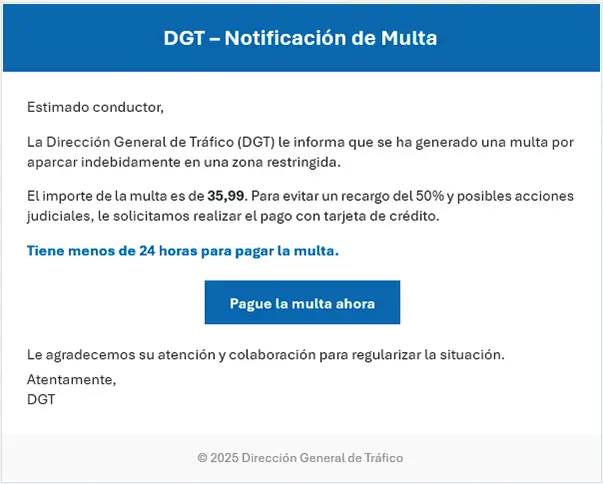

“The most common fraud continues to be fraudulent charges on accounts or cards, especially those originating through smishing and vishing,” explain Miguel Ángel López Martín, head of the Technological Crime Group in the Balearic Islands, and José Miguel Márquez, deputy inspector of the same unit. The sequence usually begins with an SMS impersonating the bank and warning of suspicious activity. The link redirects to a fake page where the victim enters their credentials. Shortly after, a call from the bank’s official number —through spoofing— requests the codes sent to the victim’s mobile phone to “cancel” the operation. In reality, those codes authorise the fraudulent transfers.

José Miguel Márquez and Miguel Ángel López, from the Technological Crime Group of the Balearic Islands.

Investment fever

Although this type of fraud is the most frequent, it is not the one growing the fastest. “The biggest increase we are seeing is in fake investments, especially those related to cryptocurrencies and unregulated platforms,” they add. On social networks, scammers pose as energy companies, banks or even public figures to lure potential investors. Within weeks, the money disappears with no possibility of recovery. The police cite the UK and Eastern European countries as the origin of many of these operations. Others, such as sextortion, typically operate from African countries or Indonesia.

Regarding the use of AI, they say that “current modus operandi work without it,” so its use is not yet widespread, although they acknowledge isolated cases and potential applications (voice cloning, deepfakes). At the same time, law enforcement is already incorporating AI to detect patterns and prioritise investigations.

Mules and a precise structure

Officers confirm that modern cybercrime is not improvised. “There is a very clear division of tasks.” At the base of the pyramid is the money mule, the holder of the receiving account. “They are often students, unemployed individuals, homeless people or drug users who participate in exchange for small sums.” Above them is the recruiter, and higher still the intermediaries. At the top are those who design the scam or develop the technological tools.

The ease of opening accounts and prepaid lines multiplies the opportunities to commit fraud. “You can go to a phone shop and buy 20 prepaid SIM cards under the name ‘Donald Trump’ —they illustrate—; or open an online account with minimal verification. These accounts are wide open to fraud.”

Once the money enters the mule’s account, it moves quickly: transfers to third parties, overseas remittances or conversion into cryptocurrencies. “If the money leaves the destination account, forget it: traceability becomes complicated. These are people who will often be convicted of fraud but will never be able to repay €40,000 or €300,000.”

If the money leaves the destination account, forget it: traceability becomes complicated.

Transnational crime and banking obstacles

The main challenge in investigating these crimes is their transnational nature. Scammers use VPNs and private networks to hide their tracks. This dispersion requires international judicial and police cooperation and slows down precautionary measures. “The perpetrators know this and use it to their advantage: they move the money extremely quickly and convert it into virtual currency to add opacity.”

Relations with banks are another friction point: some institutions cooperate, while others, according to the police, hinder preventive blocks. Regulation (EU) 2024/886 —which requires verifying the match between account holder and beneficiary in certain transfers— represents progress. Since it came into force in October 2025, operations that previously went unnoticed are now being blocked.

Time to report

After suffering online fraud, police officials insist on a simple yet decisive sequence: contact the bank immediately to request a preventive block, preserve all evidence (SMS, links, screenshots, statements) and report it at a police station or online; in the latter case, the victim must subsequently attend the police station to sign and confirm the report. Time is critical. “If the victim waits three or four days, it’s very likely the money has already left Spain.”

And the report is essential: “Without it, the incident does not exist for the authorities and patterns cannot be cross-referenced nor actions coordinated.”

“Are you going to do something?”, the victim asks. “If you don’t report it, we won’t do anything; if you do, we will try.”

In 2025, with the year not yet finished, the police headquarters had already recovered nearly €400,000. “When we manage to block the money and return it, the satisfaction is immense,” the officers say.

Most vulnerable sectors and profiles

Anyone can fall for these traps. In companies, the most common frauds are BEC / man in the middle schemes: criminals who monitor emails, insert fake invoices and divert payments. “A recent case on the island involved a company that transferred €98,000 to a fraudulent account; thanks to quick action and banking cooperation, the full amount was recovered.” In the general population, two profiles are particularly affected:

-

Older adults, less accustomed to digital channels.

-

Adult men, victims of sextortion.

Another common scam is the romance scam, which mainly affects women aged 55 to 75. This scheme is particularly damaging: months of trust-building, promises and small transfers that end up amounting to significant sums.

Cyberfraud forms an ecosystem that evolves quickly, and the Balearic Islands —due to their economic and tourist profile— are a prime target. Tools change, names vary (Alex, Daniela, David), but the same logic remains: exploiting urgency, trust and carelessness.

From social engineering to the post-quantum threat

Huguet, at the Mallorca Global offices. Photo: Piter Castillo.

Llorenç Huguet, emeritus professor of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence and director of the Cybersecurity Chair at the UIB, has spent more than four decades devoted to the mathematics behind today’s secure communications

“The evolution of online fraud has moved from the technical to the human.”

In the early days of the internet, attacks focused on servers, networks and poorly configured systems. Today, the core of the problem is something else: social engineering.

Observing habits, schedules, writing styles, forms that are completed without checking. “It’s not just technology: it’s sociology and psychology applied to fraud.”

During the pandemic, “many companies sent their employees to work from home using their own computers, which did not have the same protections as the corporate network,” Huguet recalls. “The same thing is happening now with artificial intelligence,” he warns. “We are again giving away data without really knowing what it will be used for. Maybe nothing happens today, but five or ten years from now, that information —stored now— may carry a very different value.”

The challenge will be ensuring algorithm transparency and ethical use.

The Balearic Islands: especially exposed

In a territory as dependent on services as the Balearic Islands, this nuance is significant. According to data from the National Cybersecurity Institute (INCIBE) handled by Huguet, the Balearic Islands ended 2024 as the region with the highest growth in cybercrime in Spain, with an increase in incidents and more reports from affected SMEs, which suffer average losses of around €30,000 per company.

“Service companies are very vulnerable,” he explains.

High staff turnover, non-standardised payment procedures and limited cybersecurity resources create the perfect breeding ground.

Sensorisation and automation in hotels, restaurants or buildings add another layer of risk: “Every sensor that sends data to a server can become an entry point if it’s not properly protected,” he points out.

Three fronts, one problem

The cyberfraud landscape in the Balearic Islands is not homogeneous.

On one hand, there are SMEs, which mostly suffer provider impersonation fraud, fake bank account change requests, card terminal attacks and ransomware that encrypts their systems and paralyses operations.

“Three basic defences are enough for an SME,” he summarises:

-

Two-factor authentication for payments and access.

-

Offline backups.

-

A protocol that forbids changing bank accounts without confirming it by phone with a known contact.

Meanwhile, public administrations face targeted campaigns, attacks on critical services and credential theft that can compromise data belonging to thousands of citizens. Hospitals and essential services have already been targeted in the islands.

Finally, citizens continue to fall victim to phishing, smishing/vishing, online purchase scams and fake holiday rentals. For them, the advice is as simple as it is difficult to follow: keep software updated, use unique passwords and frequently review bank activity.

The immediate future: post-quantum cryptography

In this context, the future will unfold in a less visible arena: post-quantum cryptography.

Today, many systems are considered “practically unbreakable” because cracking them would require years of computation with current machines. Quantum computing could change that rule.

“There are companies that today are capturing encrypted information they can’t read, but which they may be able to decrypt in five or ten years,” he warns.

For administrations and large organisations, this means starting to plan a transition to new standards capable of resisting future quantum computers.

“It won’t happen to me”

At user level, when asked about the most common mistake we make, Huguet doesn’t hesitate: “Thinking ‘it won’t happen to me’.” This excess of confidence coexists with a paradoxical lack of basic training.

“In the analogue world, distrust felt impolite; in the digital world, being distrustful is a form of hygiene,” he summarises. “Cybersecurity is like a seatbelt: it doesn’t prevent accidents, but it can save you when they happen.”

That’s why he insists on digital education from an early age, agreed parental control, training for families and educators and ongoing professional development for individuals and companies.

The UIB works in this direction with programmes such as CyberCamp, the Cybersecurity Chair and specific courses for SMEs and administrations. He also highlights a resource he compares to a “digital 112”: INCIBE’s 017 helpline, a 24/7 support service that guides people step by step on what to do when facing a suspected fraud or online incident.

“If we wouldn’t give a car to a minor who doesn’t know how to drive, we shouldn’t give them a digital environment without teaching them how to navigate it.”

Ultimately, he concludes, the realistic goal is not a world without cyberfraud, but a society that is harder to deceive.

Leave A Comment