Every year, some 120,000 people suffer a stroke in Spain

David Arráez. Palma

As you go over what is happening, one thought keeps hammering in your mind, incessant and rhythmic: something is not right in my head.

With the help of your wife and daughter, you make it downstairs and trudge through the house, bumping into every door frame you try to get through. More banging. More pain. Something is not right in my body.

And then you arrive at the hospital.

“It’s only vertigo. It can wait,” says the doctor on duty at Son Llàtzer. The suspicions of the triage nurse who went to look for her are ignored…

Six hours later, you are attended to. Six hours of relentless torture in which you know something is not right. Six hours of terror in which you fear that the worst could happen and that there is no turning back. Six hours of panic, of uncertainty, of guilt for all the things you haven’t done and don’t know if you’ll ever be able to do again. You are guilty of so much wasted time working, in meetings, with clients, trying to earn more money… The wasted time of a life that maybe comes to an end today and now you know what really mattered. Maybe too late.

Then a new doctor arrives, and you hear the terrible words for the first time: “It’s a Code Stroke.” And everything comes rushing in.

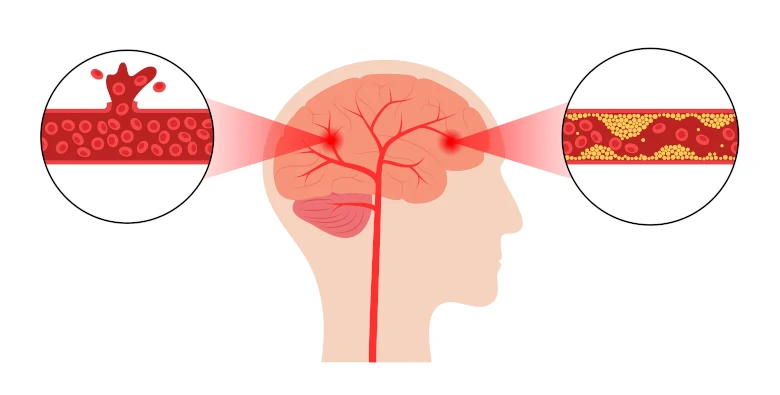

Illustration of two types of stroke: haemorrhagic stroke (left) and ischaemic stroke (right).

Eighth day of hospitalisation. Discharge. I return home with the only conclusion that we don’t know what caused the “Code Stroke.” And it’s time to start again, overcoming a tiredness that leaves you exhausted from the moment you wake up in the morning. You are not even able to go to the toilet on your own. And the fatigue continues. For days, weeks, a month, and another…

“Symptoms that have not been overcome in the first six months after a stroke are likely to be permanent.” The statement by the neurologist stuck with me.

I did not suffer from facial paralysis or hemiplegia. My speech is normal. But this eternal tiredness terrifies me. The word “permanent” does not leave my mind. This tiredness, forever…

I start to go swimming, just like when I was young. Accompanied, at first, for a few minutes. There will be many permanent things in my life, but it won’t be a stroke that will get the best of me.

As 2024 draws to a close, six months have already by now gone by. I’ve been back at work for a few weeks now, even with bouts of super-tiredness (that’s what I call it) that accompany me for a few hours and for a few days.

But many things have changed.

I swim for an hour almost every day. 2,500 metres almost every day (watch out Phelps, David Arráez is coming) and ten kilos of Mallorcanness have left me. I feel better than ever.

But the fighting goes on. At fifty-something, I still have much to live for. A lot to live for. And more desire to live than ever.

I have been lucky. Very lucky. All the luck in the world. Because my “Code Stroke” will not be permanent. Many others will not be able to tell the tale.

Right now, all I can think about is that we have to take care of ourselves. And very much so. And to learn. To learn that the most important thing in life is the only thing that, when it runs out, we can never get back: time.

Leave A Comment