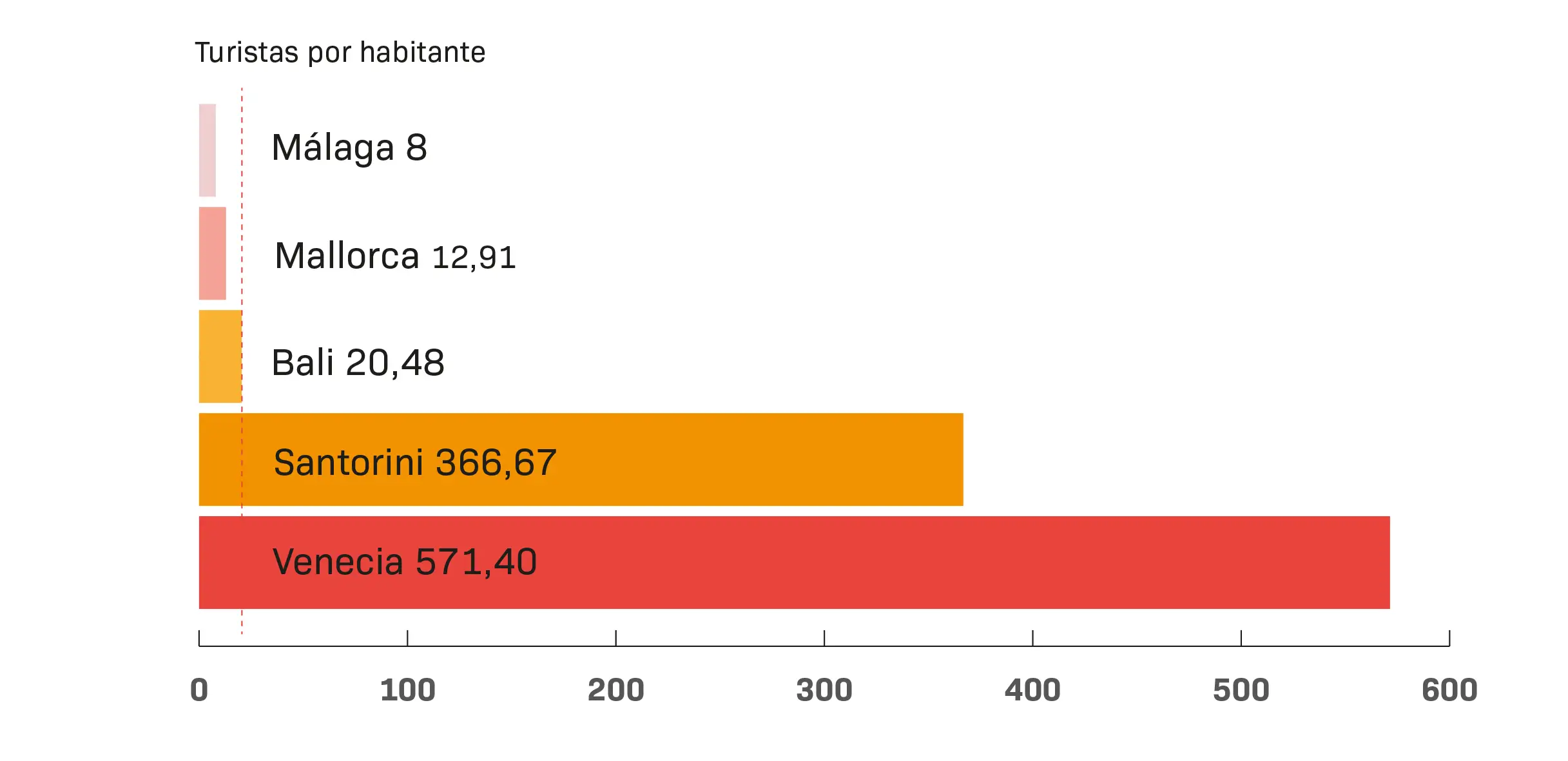

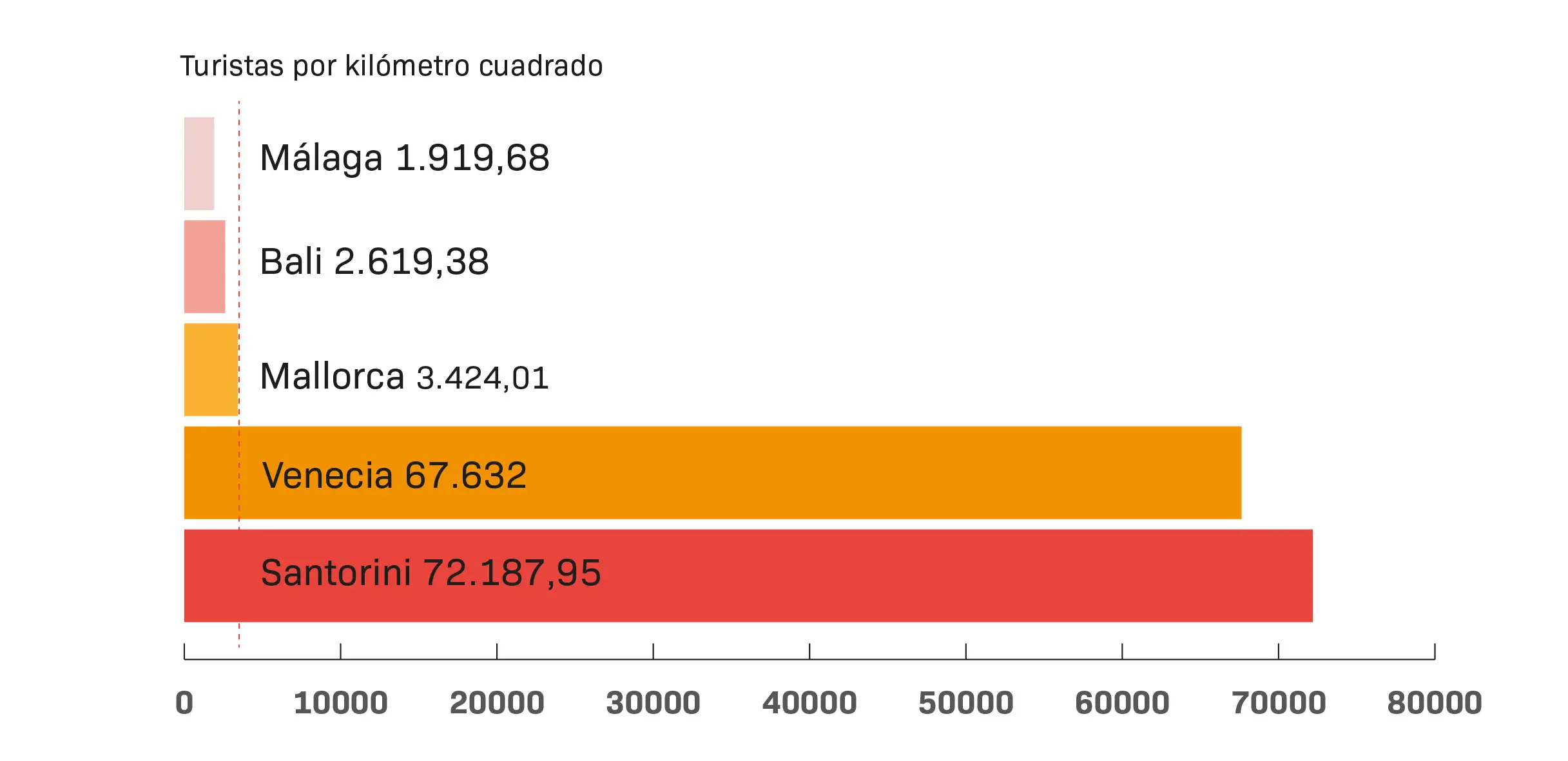

Symbol of tourist success in Europe, Mallorca has faced a growing challenge in recent years that resonates in destinations worldwide: overtourism. With over 12 million visitors in 2023, and rising, the island is immersed in a crucial debate about sustainability, quality of life, and the coexistence of residents and tourists.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Mallorca. Destinations like Málaga, Venice, Santorini, or Bali are experiencing similar pressures. However, while some areas, such as the Italian city, see their population dwindle over the years, Mallorca’s resident numbers continue to grow, placing the island at a crossroads. What can be learned from other destinations? Is it possible to balance the tourism economy with sustainability?

An image of one of the largest demonstrations held in Mallorca against overtourism. Photo: Manu Mielniezuk.

The Population Challenge

Since the start of the new millennium, Mallorca has experienced a 42.6% increase in inhabitants, growing from 677,014 registered residents in 2000 to 965,371 in 2024. This demographic boom shows no signs of slowing, as INE forecasts predict that the Balearic Islands will see the highest population growth of any autonomous community over the next 15 years. Against this backdrop, it could be said that the demographic pressure on the archipelago is in a loop: tourism breaks records year after year, attracting new residents to support the industry.

The echoes of the ‘break’ in tourism caused by the tragic COVID-19 pandemic resonate with locals in two contrasting ways: it was pleasant to recall not-so-distant times when beaches were nearly deserted, but without tourism, Mallorca’s economic situation was bleak. Four years later, the recovery has gone into overdrive, returning to the path of record-breaking numbers in tourists, human pressure, vehicles, and more.

Tourists crowd in front of Mallorca’s Cathedral. Photo: Teresa Ayuga.

Taking a Stand

Until the public finally said, “Change course, put limits on tourism,” the slogan of the second protest against overtourism held last July, which brought together over 20,000 people in Palma. This call to action highlighted concepts like containment and even degrowth in tourism but, above all, warned about the declining quality of life for residents.

Jaume Garau, vice president of Palma XXI, one of more than twenty associations that form the Fòrum de la Societat Civil for the reconstruction of the Balearic Islands, demands a “pause to this overwhelming volume of people. So many individuals, cars—almost one per resident—nature activities, marine activities, beach visitors, and road traffic… all of this wears down historic centers (with phenomena like gentrification), roads, marine ecosystems, etc.” For Garau, “it’s time to set limits or start a process of progressive reduction of tourist beds to stabilize the situation and implement the ecological transition required by climate change.”

As part of the Fòrum, Garau proposes “redirecting energy” toward other sectors and “reducing obsolete tourism and illegal vacation rentals, which are significantly harming the islands. We aren’t the only destination facing these problems, as the number of global tourists increases every year, with 1 billion more expected by 2050. This is a severe problem, especially for future generations.” However, he acknowledges that “everything operates in an international market, with poorly regulated companies driving tourism to the island and aiming for continuous growth,” from cruise lines to aviation. “From Palma,” Garau continues, “we aren’t going to solve this global problem, but if we don’t participate… We need to seek consensus, different regulations, such as protecting Mediterranean islands,” and he notes how Formentera has already begun regulating vehicle circulation. “There are examples of good practices and phenomena showing that change is possible. Mallorca will need to follow suit,” he concludes.

Global Protest

The overtourism issue not only irritates Mallorca’s residents. Mallorca Global Mag has spoken with associations and entities from other areas like Málaga, Venice, Santorini, and Bali to understand the global scale of this phenomenon, though each destination faces unique challenges.

In Greece, which is currently experiencing a tourism boom, last year saw the rise of “the towel rebellion”, a movement also familiar in Mallorca, where Greeks demanded access to their islands’ beaches. On Santorini, an island of just 76 km² and 15,400 registered residents, the emeritus professor at the University of the Aegean and director of the Aegean Sustainable Tourism Observatory, Ioannis Spilanis, remarks, “Santorini has been overcrowded for many years, and the situation is worsening.” While “last year there was stagnation—even a decline—in arrivals and a net decrease (around 10%) in tourist spending. Is this a sign of decline, as Butler’s model suggests?” he asks, referencing the Tourist Area Life Cycle theory formulated in 1980, which outlines six stages for every destination: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline.

“For now, the only measure on our island,” Spilanis continues, “concerns cruise ships: a cap of up to 8,000 passengers and a €20 fee per person. The municipality and the tourism council are pushing to halt the creation of new tourist accommodations and to reduce the number of Airbnb-style rentals, aiming to provide housing for residents and public employees.” In numbers, the Greek professor notes, “Santorini has around 67,000 beds across hotels, rental rooms, and sharing economy platforms. This equates to a pressure of 3.8 beds per resident and 881 beds/km². Adding the local population, the environmental burden exceeds 1,000 beds/km².” The overload on the Greek island is unimaginable in Mallorca. Annually, Santorini receives 680,000 passengers by sea, 1.3 million by air, and nearly 800 cruise ships, carrying 1.3 million passengers (2023).

Santorini, an island even more overcrowded than Mallorca.

The Best Tourism Year?

Closer to sa roqueta, in Málaga, protests also took to the streets in 2024. After recording its best tourism year ever in 2023 (14 million visitors), residents are demanding a “Málaga to live in, not just survive in”. Although the visitor numbers are diluted over Málaga’s area, the city faces similar challenges, such as gentrification and skyrocketing housing prices, paralleling the boom in vacation rental apartments. Among the measures proposed by protest organizers, such as the Tenant Union, are a moratorium on tourist apartment licenses, while the opposition seeks to implement a tourist tax.

The Blacklist

Seminyak, Bali, crowded with tourists.

The example of Bali (739,198 residents and over 15 million tourists annually) also shares similarities with Mallorca. Both have mid-sized island areas and face similar sustainability challenges due to their popularity. Indonesia’s tourism mecca has entered Fodor’s Travel’s list of “Destinations to Reconsider in 2025”, which included Mallorca in 2019. The travel guide describes pristine beaches “buried under mountains of garbage, with local waste management systems struggling to keep up.” The Bali Partnership Platform initiative denounces that tourists “generate 3.5 times more daily waste than residents.”

The fight to protect Bali’s environment is exemplified by the group Walhi Bali, whose pressure secured a commitment to a moratorium on building hotels, villas, and nightclubs in the island’s most crowded areas. However, this measure is still pending confirmation from Indonesia’s president.

A City Drowning in Tourism

The influx of cruise ships in Venice is a key focus of local groups fighting overtourism.

Venice has been mired in a battle against overtourism for years. The city is literally sinking under the weight of nearly 30 million tourists annually. In the ‘Serenissima,’ “Disneyfication” is already a hot topic. Unlike Mallorca, Venice’s population is steadily decreasing, to the point that what is still a city today may not be one for much longer.

One notable difference is that, according to studies, tourism in the city of canals is ephemeral: only 3 out of 10 visitors stay overnight in one of its approximately 50,000 tourist accommodations—equivalent to one per resident. As a pioneer in imposing entry fees for day-trippers, Venice continues to implement measures that appear insufficient to reverse its alarming trajectory. Recent steps include banning groups of more than 25 people, loudspeakers in the streets, and stricter cruise ship controls.

Jane da Mosto, an international consultant in sustainable development and founder of the NGO We Are Here Venice, argues that the issues of overtourism in her city “will resolve themselves once policies and the strategic management of Venice stop considering tourism as the primary income source (akin to coal mining) and stop viewing the local government’s job as organizing major events like Carnival and trade fairs.” Instead, she adds, administrations should “focus on the city’s daily life, residents’ well-being, long-term housing policies, and the health of the lagoon system,” among other priorities.

Now Is the Time

Overcrowding of tourists at Caló des Moro.

Back in Mallorca, following a turbulent year of street protests, the issue of overtourism has risen to the forefront, and – it seems – the administrations have listened to the citizens’ calls to action. The president of the Balearic Government, Marga Prohens, has acknowledged that “the time has come to make decisions” and has marked January 2025 as the month when an emergency decree will be approved as part of the Sustainability Pact Roundtable. This initiative is coordinated by Antoni Riera, technical director of the Impulsa Foundation. However, the Forum of Civil Society has suspended its participation in the Pact, citing in a statement that “this process should be an opportunity for open debate, but we perceive it as fundamentally technocratic and not participatory enough.”

As the Secretary of State for Tourism, Rosario Sánchez, states, Mallorca can “lead” a shift in Spain towards sustainable tourism. The first step, acknowledging the problem, has been taken. The next challenge is to assess the obstacles posed by an increasing number of visitors in an island already nearing its limits.

Mallorca Global Mag invites you to read more on this topic:

💡 Interview on overtourism in Mallorca with the Minister of Tourism, Jaume Bauzà.

💡 The Secretary of State for Tourism, Rosario Sánchez, speaks with Mallorca Global Mag.

Leave A Comment